The Fifth Estate is a new power born from the rise of the Internet as a new geography of governance. It embodies the "planetary thinking" theorized by Yuk Hui, representing the Total Mobilization of Network Power to shape our world. It is sovereign, because it is immune from any single nation’s control, and upheld by the consent of its participants. This vast, decentralized system has yet to realize its full potential.

Outline

2.1. Network and Nomogenesis

2.2. Defining the Fifth Estate

2.3. Members of the Fifth Estate

2.4. Sovereignty of the Fifth Estate

2.4.a. Sovereign Immunity

2.4.b. Popular Sovereignty

2.5. Big Tech and the Countervailing Power

2.6. The Fifth Estate in Action

2.6.a. The Fifth Estate in Crisis: Taiwan Case Study

2.6.b. The Fifth Estate for Nation States: Estonia Case Study

2.6.c. Peak Fifth Estate: Wikipedia Case Study

2.1. Network and Nomogenesis

Of the two forces which shape civilization the most, Space and Information, Space is arguably the most determining factor in elucidating questions of sovereignty. In his seminal text, “The Nomos of the Earth”1, philosopher, jurist, and geopolitical realist Carl Schmitt delivered a profound meditation on space and the geography of law. Schmitt argued that Nomos, a Greek word signifying law or custom, emanated from the land, specifically the acquisition, partition, and dominion of land by the state.

Schmitt claimed that “the great primeval acts of law” are “terrestrial orientations: appropriating land, founding cities, and establishing colonies.” This makes international law the outcome of a process of drawing lines on the Earth. Schmitt’s focus in the book is on those transitions which reconstitute those borders and how space as a concept itself changes over time, reframing the nature of governance in the process.

Figure 1: The dominion and conception of Space dictates law and governance (Nomos).

Author P. J. Blount’s “Reprogramming the World: Cyberspace and the Geography of Global Order”2 reveals the gaps in Schmitt’s thinking, however. Blount believes that Schmitt’s account of Nomos is too strictly tied to the land, arguing instead that in a networked world, Nomos “must be understood as being linked not to land but to geography as mapped by human understanding of the spatial condition”. Blount argues:

Cyberspace maps reflect spatial characteristics in terms of devices and users, placing devices and users as the external boundaries of its legal and political geography and reflecting the interoperability of open architecture networking. These visualizations depict an alternative geography in which the “power to control activity in Cyberspace has only the most tenuous connections to physical geography.”... The idea of the border is unhinged from territory, which calls for reconsideration of spatial, legal, and political geography.

Schmitt himself understood how technology redefines the spatial and legal order, seeing America’s command of airspace in his time as the seed of future Nomoi. But his analysis doesn’t consider the issue of technology deeply enough. Instead it is Blount, by way of Schmitt, who arrives at the undeniable conclusion that with the Internet—what Blount calls Cyberspace, and what I will refer from here on as the Network—we are witnessing the birth of a new Nomos of the Earth.

According to Blount, the Network is not, like the idealists and anarchists suggest, borderless. As geopolitical realists rightly insist on pointing out, it is a physical infrastructure that traverses the territories of sovereigns, and its users are undeniably subject to these territorial laws. However, the realists also misunderstand the true nature of the Network, overlooking the extent of its integration into society (linguistically, socially, and politically) and the state's limited control over it.

The Network is deeply embedded in all aspects of daily life and is endogenous to social and political processes, shaping culture and political consciousness, and in turn challenging traditional notions of territoriality. Here is Blount again:

Cyberspace architecture allows users to experience borders differently thereby reconstituting the social understanding of those borders…This observation places technology as central to the transformation of space through social experience. Thus, while borders maintain a “physical obdurate premodern signature,” the power they contain “is networked virtually” and the people they contain are “hybridized.” Interoperability renders standards as “non-tariff barrier[s]” which eases interaction across these fortifications.

This integration suggests, according to Blount, that the Network is more akin to a river than a highway—an integral part of the landscape that is hard to regulate strictly. Consequently, the Network requires a rethinking of legal and political geography, as its nature undermines the concept of strict territorial borders. The logical conclusion of the hybridization caused by the Network is the gradual erosion of the nation state as a “middle man” between the local and the global. The result is that the city and the planet will become the primary centers of governance this century.

The rise of the Network, an as yet “unconquered” and ungoverned space, represents a Copernican turn: the decentering of Westphalia (the absolute authority of nation states) in favor of the poly-centricity of the Network. This Nomogenesis is one of the most central trends of our time. As of now, the realists are winning, because as an alternative geography, the Network is still “filtered through local languages and meaning systems.” Thus despite this spatial shift, the international remains a powerful force. My claim in this essay is that this shift can only happen with the recognition of those who populate and animate the Network as legitimate actors in the governance of our planet. It is this “constituency” born from the Network which I call the Fifth Estate.

2.2. Defining the Fifth Estate

The term Fifth Estate is an evolution of the estates framework derived from the French Ancien Régime‘s three estates of the realm: the Clergy, the Nobility, and the Commoners. Today, these three estates are reframed as the three branches of government common in most nation states: Legislative, Executive, and Judicial. It is widely accepted that the Fourth Estate represents the press, journalism, and mainstream media: a fourth power designed to check the other three.

Figure 2: The Estates of the Ancien Régime.

Figure 3: The Modern Estates Regime.

It is useful to note how hard winning this mantle of “Fourth Estate” was, and how new the “freedom of the press” really is as an idea. It was as recently as 1766 that the first Freedom of the Press Act, which barred the Swedish government from censoring print media, was passed. Thousands of years prior, government censorship of information was not only common, it was seen as a divinely ordained norm.

Today, nobody would deny the legitimacy of the press as a power in its own right. Crucially, this notion that the press should be free could only maintain in a world after the printing press was invented.

The Network has existed for over 30 years now. But just like the Fourth Estate before it, the Fifth Estate will have to earn its power and legitimacy. The first step to achieving that is for the Fifth Estate to recognize itself.

So let us offer a rough definition of the Fifth Estate:

The Fifth Estate is the fifth power — a planetary-scale network that derives social, economic, and political power from the Internet.

Figure 4: The Fifth Estate.

Due to its nature as a planetary network, the Fifth Estate literally envelops and contains the old Nomos of land from which it was birthed. The Fifth Estate is therefore everything. It is part of the accelerating process of Planetarization3 theorized by philosopher Yuk Hui. Hui defines this concept as the “total mobilization of matter and energy” made possible by technological acceleration, viewing it as a source of chaos, danger, and hope. But rather than dehumanizing or “enframing” humanity, as Hui believes Planetarization does, the Fifth Estate is a conscious attempt to give Planetarization a human face. That is, to embody a “planetary thinking”, as Hui calls it, characterized by the practice of using technology to mediate increasingly human, nonhuman, local, and planetary relationships.

The Fifth Estate should therefore be understood as the Total Mobilization of Network Power to shape our growing planetary condition.

2.3. Members of the Fifth Estate

The Fifth Estate numbers close to five Billion people—easily the largest country on Earth if it chose to be one.

Figure 5. Source: Our World in Data.

It is composed of the individuals and groups who create and distribute digital technologies and media, as well as those who use said technologies to achieve individual and collective goals. So far, the long history4 of the term ‘Fifth Estate’ has defined it as alternative social media, blogging, and overall internet publishing. This is a myopic view of an infinitely more powerful entity. The purpose of this essay is in fact to appropriate and expand the notion of the Fifth Estate. In its truest, most material form, it is a network which includes, but is not limited to:

Technology philosophers, researchers, and anthropologists

Founders of technology companies and/or open source projects

Contributors to technology companies and/or open source projects (designers, engineers, etc)

Digital press and social/alternative media producers and consumers

Content creators, curators, and moderators

Early adopters of digital technologies

Digital communities and crypto networks

Digital natives (digital nomads, e-residents, remote workers, Bitcoin holders, stablecoin users)

A simplistic heuristic to determine if someone is part of the Fifth Estate is to see if they have ever used the Network to say anything, do anything, or hack anything. Unsurprisingly, billions have done so, for the Fifth Estate is a world of its own, where the tasks, economies, and relationships which were typically confined to the national layer are increasingly redistributed to the Network.

2.4. Sovereignty of the Fifth Estate

The Fifth Estate is a sovereign power in its own right for two reasons: 1) The Network is not terra nullius (no man’s land). It is populated by as many as 5 billion souls, and thus “claimed” daily by its participants. Further, by virtue of the mobility of its settlers, the Network enjoys virtual immunity from the dominion of all competing earthly sovereignties; 2) The Fifth Estate operates via consent of the ‘governed’, an internationally accepted standard of sovereignty, manifested by the voluntary participation and permission-less nature of the Network.

Sovereign Immunity

In the first case, no nation state or international organization can unilaterally shut down the Internet. Such a move is not in the interest of any government, given that they all need it for surveillance and intelligence purposes. Certainly, draconian regimes or developing countries can and often do stop their own citizens from accessing the Internet and impose regulations, but only imperfectly.

Further, not only can such measures be bypassed by digitally savvy groups and individuals, they often produce a mass digital exodus from said governments as citizens begin quietly disengaging from their country of birth, choosing instead to hold their assets in digital currencies5, or use the Fifth Estate to directly oppose local sovereigns.

In Guinea, for instance, where the current dictatorship has repeatedly shut down internet access and banned the local press (the Fourth Estate), young men and women have leveraged their connections across the Guinean diaspora to produce dissident media channels on YouTube, such as EspaceTV6. The latter has almost 200,000 subscribers, and live streams daily to all Guineans around the world, keeping them informed about the happenings in their country—a direct and consistent violation of the dictatorship’s sovereignty.

Popular Sovereignty

Further, as modern standards of sovereignty attest, true sovereignty flows not just from the barrel of the gun, but from the consent of the governed. The Fifth Estate has grown to include billions of people, none of whom had to be persuaded by force to participate, without any central organ of coordination. Even phenomena like “cancel culture” are a canonical, if pathological manifestation of the Fifth Estate’s sovereignty, just as the mob was for the Third Estate during the French Revolution.

Henry Kissinger, as deep a geopolitical realist as any figure in the last 50 years can claim to be, did not himself believe in the inviolable right of the nation state to overpower its citizens in pursuit of its interests. In reference to the treaty of Westphalia which enshrined the principle of national sovereignty, Kissinger claimed instead that while “the right of each signatory to choose its own domestic structure and religious orientation was affirmed…novel clauses ensured that minority sects could practice their faith in peace and be free from the prospect of forced conversion.” Meaning, as foreign policy expert Anne Marie Slaughter has pointed out, that Westphalia proclaimed the equal sovereignty of states not for its own sake, but to safeguard their people.

Currently, according to the standard of international relations, the only legitimate actors on the world stage are sovereign nation states. The treaty of Westphalia and the 19th century spread of nationalism have constructed the myth of international space as a system of territories with centralized states lording their authority over every claimed or unclaimed patch of Earth. Only states can act within this space, and it is fundamentally states’ rights, legitimized by territorial sovereignty, which are privileged globally.

Even after the rights of individuals became enshrined following Nuremberg and the birth of the Human Rights convention, the reality is that the rights of peoples are still a suggestion in international law, and secondary to the rights of sovereign states, who are the ultimate arbiter of human rights within their borders. This has made popular sovereignty a mere symbolic notion in a world dominated by technocratic international institutions, gigantic corporations, and centralized states. But in the 21st century, through the rising Nomos and geography of the Network, a case can be made for a source of legitimacy which can rival that of nation states. The Network, a space where popular agency can reign, ensures that what was once a symbol can be made real.

2.5. Big Tech and the Countervailing Power

Internet pioneers like Barlow feared early government meddling, quite rightly. But what they missed was a much greater, and more pernicious danger: corporate control of the Network. Such an oversight from the early ‘cyberspace’ thinkers was a sign of the times, with Communism's fall and market utopianism in full swing.

The result, unfortunately, is that Big Tech rules the digital world now. These companies are the most powerful private forces on earth. They shape free speech, national security, and public policy. While fearing government overreach may have been wise, it was not prescient, for the real threat to the Fifth Estate's sovereignty will surely come from Big Tech.

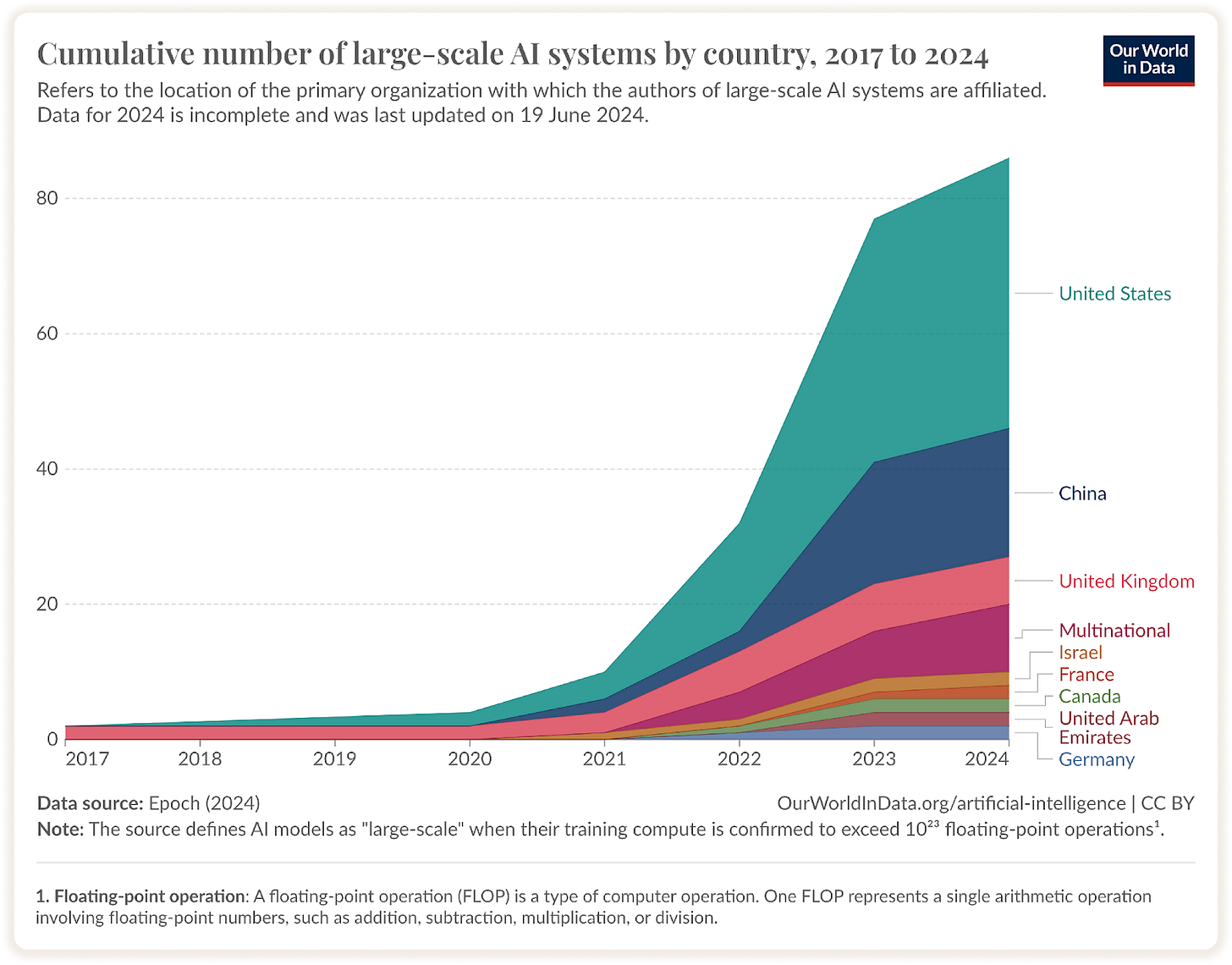

We see the same trends emphasized in the rush from AI executives to preemptively regulate the technology; a feat that promises to entrench the monopoly of the trillion dollar behemoths who foot the bill for the production of these systems, as smaller companies cannot pay the multiplying costs of compliance.

Figure 6. Source: Our World in Data.

This is the dawn of an AI-National Security Industrial Complex. Within the decade, it is likely that a marriage between domestic AI labs and the national security state will produce an AI oligarchy that will concentrate most of the gains from this technology among itself. The flaws of Barlow’s libertarian approach are clear: it only leads to retaliatory statism.

John Kenneth Galbraith wrote that “Private economic power is held in check by the countervailing power of those who are subject to it…The first begets the second.” Adapting Galbraith to this moment, we would state that “Big Tech can only be held in check by the countervailing power of those who are subject to it”. If the last decade has seen the state fumble in this task, my claim is that the next candidate for a countervailing power has been found in the Fifth Estate.

2.6. The Fifth Estate in Action

The Fifth Estate in Crisis: Taiwan Case Study

Fire destroys, but can also cleanse. While the pandemic uncovered the tyrannies we collectively tolerate, it also showed that some shining cities still light the way forward. This was the example of Taiwan, which in the early days of the pandemic had one of the lowest COVID death rates in the world, and largely avoided unnecessary lockdowns, preserving the freedom and sovereignty of its citizens throughout. The way Taiwan did this is perhaps the clearest foreshadowing of how the Fifth Estate might operate at scale.

Taiwan moved swiftly when the pandemic began because a keen health official noticed a popular post on a forum about a new disease in China. This very fact highlights why government leaders so willingly and eagerly cooperated with the Taiwanese Fifth Estate in the uncertain and critical early days of the pandemic.

Civic hackers pounced at the chance to build infection maps and bots to distill digital signal from noise, and cooperated with health officials to survey all corners of the Internet for news. They leveraged government health data and surveyed migration patterns to track the mobility of the disease. This worked because of the high level of trust among the public and its institutions, particularly Taiwan’s g0v program, a decentralized civic tech collective of open source contributors and Silicon Valley veterans which acts as a frequent government partner.

The effect for Taiwan has been the creation of a seamless digital governance system that still endures. In the West—where similar Fifth Estate efforts arose in the beginning to both warn the public of the pandemic, and when it was shown to be less harmful than expected, recommend relaxed measures—the response was moot, as all decision making power was centralized within the expert class and organs such as the CDC. Against this failure, and beyond the pandemic, Taiwan’s recognition and integration of the Fifth Estate into its governance apparatus heralds what’s to come.

The Fifth Estate for Nation States: Estonia Case Study

Network Power is not just a tool for the Fifth Estate. As the case of Estonia shows, when properly leveraged, it can be deployed in the service of dynamic and astute nation states to achieve domestic interests.

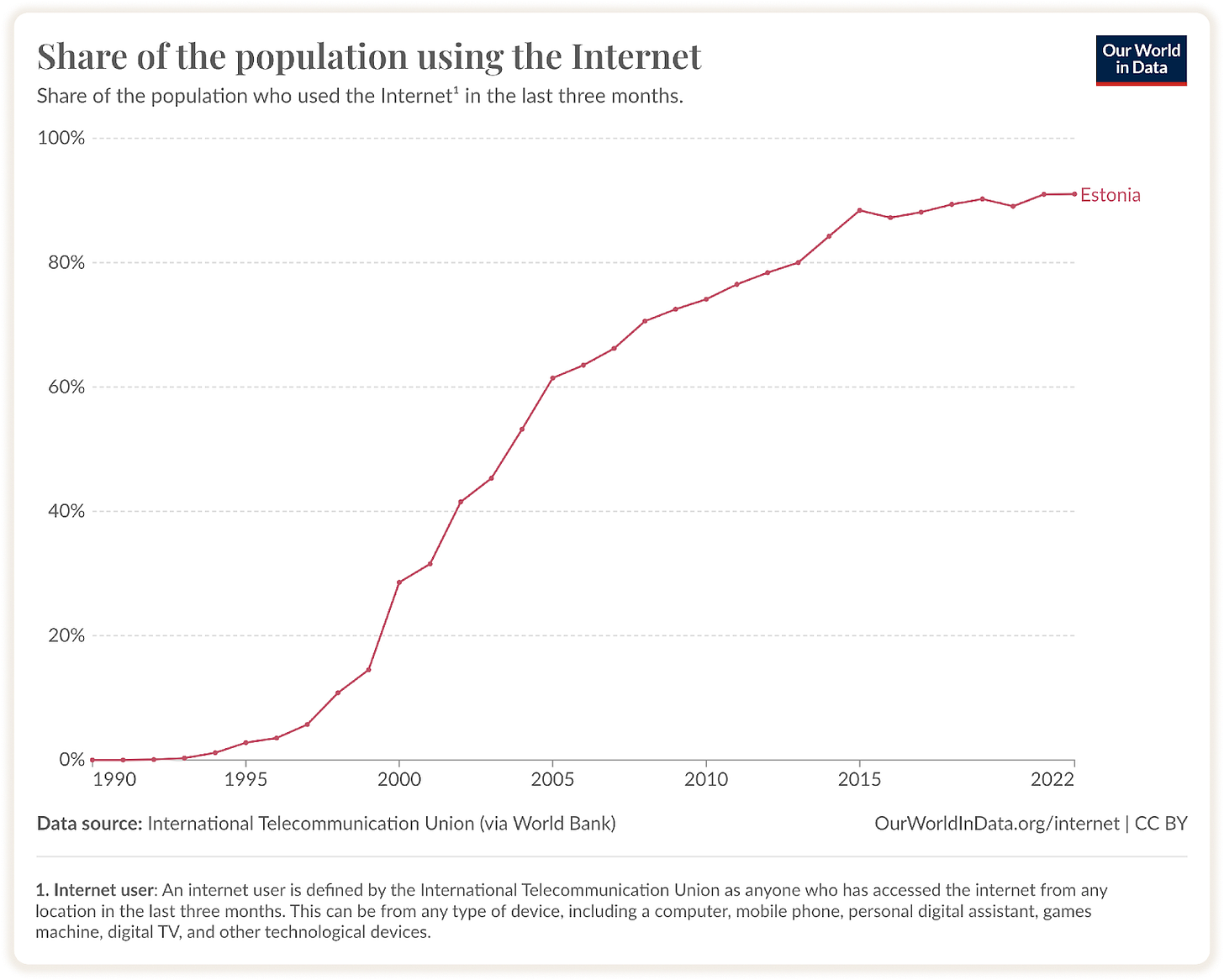

Over the last 20 years, Estonia has become the undisputed world leader in digital governance, offering a real-world example of how a country can leverage Network Power to enhance citizen services and participation.

Figure 7. Source: Our World in Data.

The country’s digital identity system provides every Estonian citizen with a digital ID, making virtually all public services accessible via the Network. Citizens can see who has accessed their data, enjoying the full transparency only possible with Network Power. And with such critical infrastructure, Estonia has successfully implemented online voting in national elections since 2005.

Through an e-Residency7 program offered to non-Estonians, Estonia enables anyone with an internet connection to start and run a global business in the EU. Their use of blockchain technology to secure health records and other sensitive data is a massive legitimating factor for the future of cryptographic coordination technologies.

Figure 8. Source: Our World in Data.

These measures, carefully built up by the Estonian government since 1997, are reported to save the country over 1400 years of working time and 2% of GDP annually. It has made the country extremely resilient, as the New Yorker writes:

In the event of a sudden invasion, Estonia's elected leaders might scatter as necessary. Then, from cars leaving the capital, from hotel rooms, from seat 3A at thirty thousand feet, they will open their laptops, login, and—with digital signatures to execute orders and a suite of tamper-resistant services linking global citizens to their government—continue running their country, with no interruption, from the cloud.

Indeed it appears the first truly immortal countries will be those that fully exist within the Fifth Estate. If these measures were implemented in the United States, the country would have almost $500 Billion extra to put towards better public services, energy and technology investment.

Peak Fifth Estate: Wikipedia Case Study

Humanity’s capacity for acclimating to escalating levels of excellence is an astounding thing, but can also stop us from seeing true greatness when faced with it. Wikipedia’s resounding success in achieving its mission to codify all the world’s knowledge in a free, globally accessible digital encyclopedia, is arguably the greatest achievement of the Fifth Estate to this day. A decentralized effort to create and curate knowledge, diligently, over decades, and in the face of repeated attacks8 on its legitimacy and credibility—Wikipedia is arguably the 8th Wonder of the World, or the First Wonder of the New World. It is the clearest manifestation of Network Power at its purest.

Launched as a side project of Nupedia, a free digital encyclopedia startup that had only produced 21 articles in a year by following the old publishing methods, Wikipedia succeeded precisely because it thwarted all the expert conventions for curating knowledge. By the end of its first year, the side project had produced articles on 18,000 different topics.

From its inception, anyone could contribute to Wikipedia, regardless of credentials or location. The project was self governed, developing its own arbitration and editing policies. Perhaps the most revelatory aspect of the encyclopedia was that it was alive: articles were updated constantly to reflect changes in the world, outcompeting traditional encyclopedias stuck in the old publishing model. Sixty million articles and 4.3 Billion daily visitors later, these counter-intuitive choices have proven more than fit for purpose.

Available in 300 languages, Wikipedia is accessible almost to the entirety of the Fifth Estate, which has enabled it to remain one of the most visited websites globally, and a reputed source of knowledge at every level of society. It is truly Network Power at its peak. Of course, Wikipedia is not without its flaws. There have been reports of ideological capture9 among the editing corps, concerns over its repeated fundraising controversies10, and debates over its ability to keep pace with technological change.

For the Fifth Estate, however, the question which Wikipedia poses is whether or not similar feats of coordination to solve challenges more complex than global knowledge curation and dissemination can ever be repeated. I believe they can. But for that to happen, the libertarianism of the early Internet era will have to give way to a more consciously coordinated system.